|

Author(s) / Origin of Letter

|

Recipient(s) / Relationship to Author(s) / Destination of Letter

|

Summary

|

|

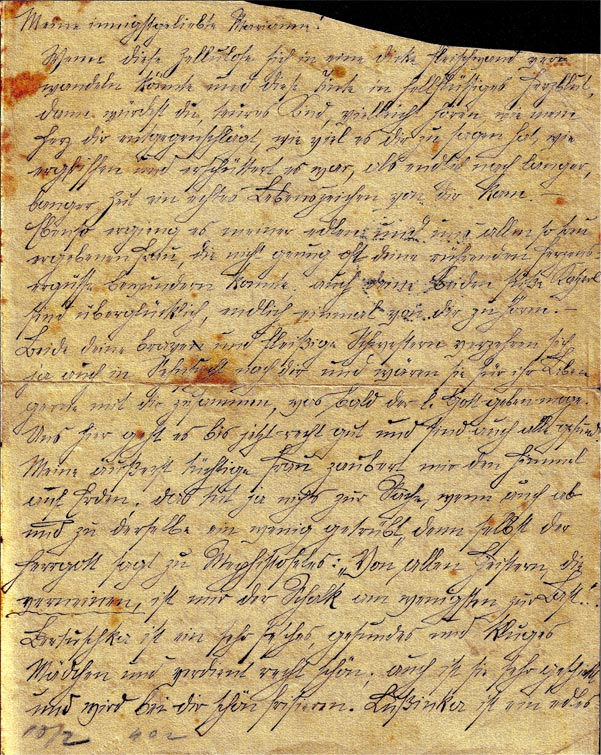

Hugo Jellinek

Gisela Jellinek Schlesinger Fritzi Fränkel (Hugo’s new wife) Anna Jellinek (Hugo’s youngest daughter) Heinz Rosenzweig (Fritzi’s nephew) [Brünn, Czechoslovakia] |

Gisella Nadja Jellinek (daughter of HJ, niece of GJS, sister of AJ, stepdaughter of FF, cousin of HR, by marriage of HJ to FF) |

This letter corroborates that the persecution of Jews in Brünn had still not progressed far by late 1939 or early 1940. Among the optimistic statements that are especially poignant in light of the writers’ tragic fates, are: Hugo’s praise of the good life Fritzi is providing him and of the blossoming of his daughters, Berta and Anna, his citation of what God said to Mephistofeles in Goethe’s Faust, news of Berta’s preparations to join Gisella Nadja soon in Mandate Palestine and the plans for Anna, Hugo and Fritzi to come later. Hugo and Anna also express deep love for Gisella Nadja and great joy at having received mail from her. |

|

My dearly loved Marianne,2 If this cellulose stuff could change into a thick meat sausage and The same thing happened to my noble and to all-of-us-devoted, to Mephistofeles: |

|

||

|

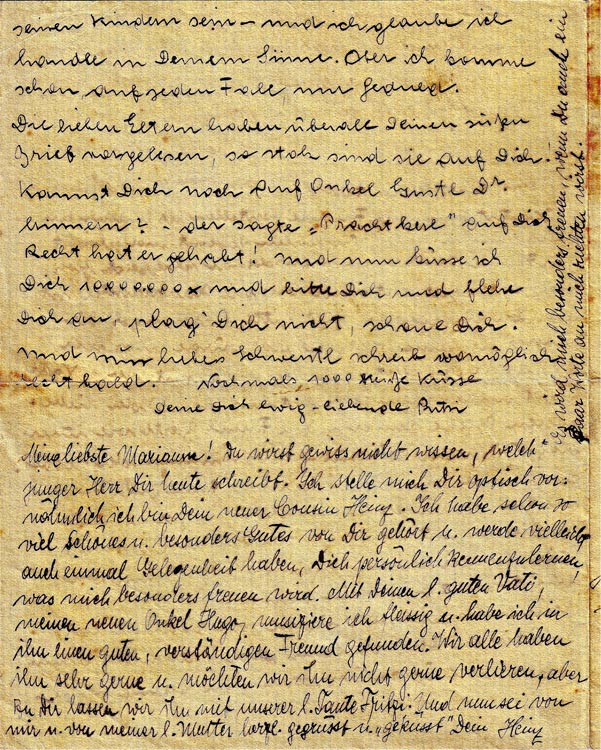

[page 2]

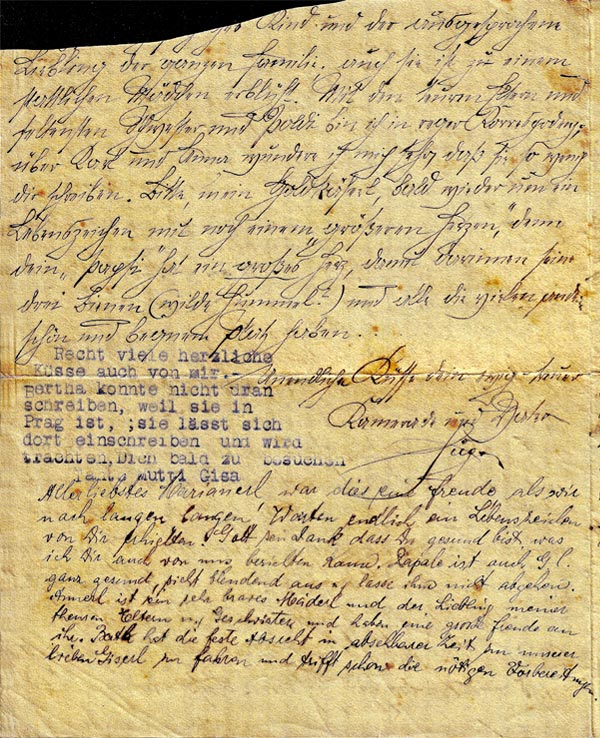

[. . . ? . . . 6]. child and the definite darling of the whole family.

Much loved Marianne, |

|

||

|

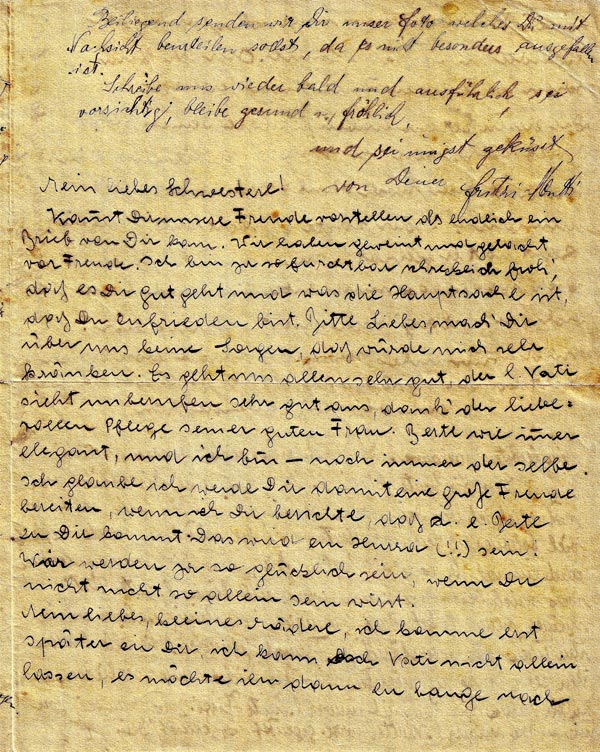

[page 3] Enclosed I am sending you our photo, that you should judge with Write to us soon again and in detail, be careful, stay well and

and I kiss you sincerely, from your Mama-Fritzi My dear sister! Can you imagine our joy when a letter from you arrived at last. |

|

||

|

[page 4]

about his children – and I think I am acting the way you would Again, 1000 ardent kisses, Your forever-loving Putsi13

My dearest Marianne! I am sure you don’t know which young man

[written along the right margin] |

|

Translated by Anne L. Fox; parts edited by Daniel Gillis and John Cary

Footnotes

1. We believe that this letter was writtten soon after Hugo and Fritzi’s marriage of October 22, 1939, and probably before the end of January 1940, because of the following: Hugo and Anna refer to Fritzi as Hugo’s “wife,” Fritzi’s signs her message to Gisella Nadja as “your Fritzi Mama,” Fritzi’s nephew, Heinz, refers to himself as Gisella Nadja’s “new cousin” and to Hugo as his “new uncle,” and Heinz’ introduction’ to Gisella Nadja in this letter seems to precede his message to her in the composite letter of January 15, 1940 (to be posted to this website in the future).

2. Hugo, Fritzi and Heinz addressed their letters to “Marianne” to disguise the fact that their letters were really meant for Gisella Nadja. Marianne Robicek, Gisela J. S.’s long-time, school friend, was the secret conduit for many of the letters to Gisella Nadja.

3. The late John Cary, Haverford College Emeritus Professor of German Literature, enabled me to understand Hugo’s (perfectly accurate) quotation of this line, from Part I of Goethe’s Faust, as follows: Hugo is being optimistic and making light of Hitler, by alluding to him as a simple rogue, who is the least worrisome or troublesome. Goethe writes that the rogue is the least “onerous” because the rogue is a simpleton whose temptations are obvious. He is not the devil of absolute evil, of moral laxness and inaction, and he is not victorious in the end in gaining the soul of Faust. Hugo’s use of this line, that is optimistic overall, (as well as idealistic, romantic and passionate) about mankind and life, could mean that Hugo is still optimistic, or that he is trying to bolster his own optimism and/or reassure his daughter Gisela Nadja.

The translation of the quotation is by Walter Arndt in the Norton Critical Edition of Faust.4. Bertuschka was the Russianized, affectionate nickname of Berta, Hugo’s ‘middle’ daughter.

5. Lussinka was the Russianized, affectionate nickname of Hugo’s youngest daughter, Anna Luchia.

6. The top left corner of the paper is cut off here, rendering illegible, what must have been another postive adjective describing the “child” Anna. This missing piece of the paper, is most likely the result of the censors’ cutting away the date and city name, that would have been written in this top corner position on the reverse side. There are two censor marks, “10/2” [?] and “402,” at the bottom left corner of the first side, which is one of four sides created by folding the whole piece of paper in half.

7. Poldi was the nickname of Leopold Schlesinger, the husband of Gisela Jellinek Schlesinger and thus, Hugo’s brother-in-law.

8. Karl Jellinek was Hugo’s younger brother who had escaped from Vienna to New York City in February 1939. The Anna that Hugo is referring to here, is Anna Jellinek Nadel, Hugo’s younger sister, who had escaped from Vienna to Sydney, Australia in January 1939.

9. We can assume that Gisela, as well as Hugo, Fritzi, Anna and Heinz, deliberately do not explicity name “British Mandate Palestine,” because of their fears of a negative reaction from the Nazi regime censors.

10. Fritzi seems to imply here that she won’t let Hugo leave Brünn (for Mandate Palestine) because he is now “quite healthy [and] looks wonderful.” Today, we can see how tragically ironic her thinking was and how revealing of what she, Hugo and so many others couldn’t yet know, of the “. . . entirely new and utterly horrifying reality” that the near future would hold for them. Please see the end of this website’s Introduction for a more complete version of this quotation from Saul Friedländer’s Nazi Germany and the Jews, Volume 1: The Years of Persecution, 1933 - 1939.

11. “Knock on wood” is the closest translation to the German word, “unberufen.” that Anna used here. A New German and English Dictionary by Karl Breul, Funk & Wagnalls Co., NY & London, 1914, states that “unberufen” is a superstitious exclamation to ward of evil, after speaking favorably of something. When I heard my parents say “unberufen,” I was able to glean from the context only that my parents were praising me about something positive that I had achieved or done, along with some admiration and gratitude for it. Anna used “unberufen” here, similarly; but she probably knew about the superstitious aspect of this word, that I , growing up, did not.

12. Bertl refers to Anna’s older sister Berta. Adding the “l” is in accordance with theYiddish language’s formation of a diminutive, and often affectionate, version of a name or object.

13. “Putsi “, along with “Lussinka” were affectionate nicknames for Gisella Nadja’s youngest sister, Anna Luchia.

14. Heinz Rosenzweig was a nephew of Fritzi Fränkel. Thus, by Fritzi’s marriage to Hugo, Heinz also became Hugo’s new nephew and Gisella Nadja’s new cousin. I could not find Heinz in the victim data bases of Yad Vashem or the US Holocaust Memorial Museum, but it is most likely that he met the same tragic fate as his mother and all of his new relatives.